Last Updated on September 1, 2023

It has always amazed me how few high school Art students use a ‘ground’ in their artwork. While grounds are common in contemporary art, many students continue to draw or paint solely on unprimed, undecorated surfaces (usually plain white paper). This approach can be wholly appropriate – and, indeed, sometimes wondrous – however, for many projects, there are considerable benefits to being creative with the treatment of a painting surface (as there is in painting or drawing onto different materials, which was discussed in Part 1 of this series). This article shows you how to integrate a ground within your artwork and illustrates just how beneficial this technique can be.

A painting by Andrew Young completed on a dripped, mixed media ground:

What is a ‘ground’?

Short for ‘background’, a ground is the very first layer of paint (or other wet medium) applied to an artwork. It is an undercoat, which can either be covered entirely by subsequent media, or left visible in the final work.

Using a ground has several practical advantages, as well as some important aesthetic ones. For example:

- Blending colours is easier. Most papers, canvases, timbers and fabrics are very porous. If you paint directly upon them, the moisture from the paint is absorbed almost immediately, resulting in paint that is difficult to spread and difficult to blend.

- Paint dries richer and more vibrant. Without a ground to ‘seal’ a surface, paint dries prematurely and becomes slightly flat and dull in appearance; absent of its natural glossy sheen (if you have never used a ground, you won’t be aware of how full-bodied and beautiful paint can look when it is allowed to slowly evaporate dry).

This painting by artist Kim Naumann has been completed on a collage of textured paper, such as wallpaper and gift cards. The blue and brown washes over the top has settled in the creases and indentations, highlighting the texture and creating a beautiful ground for the painting. - You can paint on a greater range of surfaces. Many shiny materials, particularly composite boards (such as hardboard, which contains oil) repel acrylic paint. A professional primer such as Gesso (see below) is designed to adhere to such surfaces and to create a ground that is perfect for painting upon.

- Texture. A ground can be used to smooth over imperfections in the underlying surface or to create new texture.

- Flimsy papers can be strengthened. A sheet of paper becomes stiffer and more resilient when covered with a thick ground (sometimes painting both sides is necessary, in order to minimise warping). A sturdier piece of paper is especially beneficial if later adding collage or heavy elements to a work.

This painting by artist Ian Francis has been painted on a black ground. Black forces you to apply thick (or many) layers of paint and it can help create deep, brooding shadows. - It allows you to easily cover underlying colours. A thick primer reduces the number of layers needed to cover a intensely coloured surface.

- Paintings can be finished faster. If a ground remains partially – or completely – visible in a finished work, the painting can often be finished much faster. At a very simple level, your work is already partially done: the canvas is covered entirely from the start (time is usually of vital importance for high school art students who are obligated to complete work within tight time frames – if you need more tips for increasing your work speed, please read How to Paint and Draw Faster).

- Paintings can look more ‘authentic’, as if they belonged to a ‘real’ artist. Why? Because grounds encourage layers and in doing so, give a greater opportunity for the artist to really interact with the work; their soul to be tangled within it. Layers give history and depth.

Image sources: Kim Naumann, Alexander Pavely, Ian Francis and Sam Winston (below).

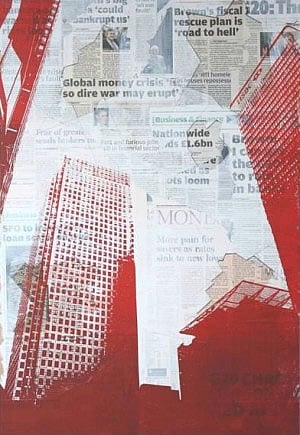

A striking painting by Michael Shapcott:

A Guide to Painting Grounds

Gesso Grounds

Gesso is a professional primer (a paint-like product that has been designed specifically for preparing a painting surface). It binds well to a range of materials and has a chalky texture that is great to paint on. It is usually thinner than paint (so spreads over larger areas easily) although different brands have different consistencies. Extra thick varieties can also be used to create sculptural effects or sanded to a smooth finish. (I recommend Atelier gesso).

A gesso ground is generally advisable whenever you are painting on something that is extra absorbent or paint-resistant. It is not necessary with most papers (although it can be advantageous, for the reasons listed above).

Gesso is typically white, however it comes in a range of colours as well as black and clear, and can be mixed with paint to create other colours.

Note: Gesso doesn’t have the same glossy ‘finish’ as acrylic, so it is generally not suitable for leaving as part of the finished visible work, unless covered with a protective surface such as glossy impasto gel or varnish.

Coloured Grounds

When selecting a coloured ground, it is advisable to use a colour that will be prevalent in the painting, as in the example below by Adrian Gottlieb.

Acrylic Grounds

If you don’t have access to Gesso, pure acrylic paint (of any appropriate colour) can be used to create a ground. This can be cheaper and more convenient, as most students have a supply of acrylic paint to hand, however it creates a glossy surface that is sometimes difficult to paint or draw upon (although some people prefer the slicker surface to gesso’s chalky texture). Watering the paint down (see below) will eliminate this problem.

An acrylic ground can also be used over the top of gesso, or to under-paint specific areas, as in the example by Linda Mann below.

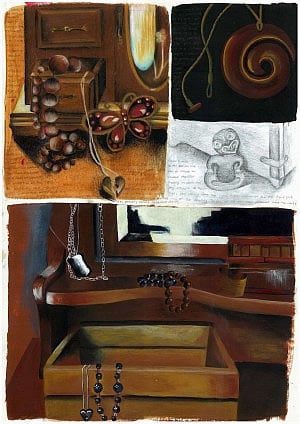

Solid acrylic grounds (as well as other grounds described on this page) can form an integral part of an IGCSE / GCSE and A Level Art project. In the outstanding International GCSE sketchbook page shown to left (completed by Nikau Hindin while studying at ACG Parnell College) – part of an IGCSE Art and Design Coursework project that achieved 99% – three of the four studies have been completed upon an acrylic ground. Note that the edges are ragged and uneven, helping to create the feeling of an experimental ‘work in progress’, as is typical of a sketchbook page. As mentioned above, the colour of the each ground is the most common colour in each individual work, with large areas of the ground left visible at completion. Having a ground visible in the final work clearly speeds up the painting process – a factor that is very important for A Level Art students.

The artwork to the left by Lyndon Hayes shows a contemporary approach to a ground. Not only is the brown a useful mid-tone for the flesh of the runner, a large expanse is left visible in the foreground of the work.

Messy, Textural Grounds

The real fun with grounds occurs when you begin to treat them with as much enthusiasm and dedication as you give the subject of the painting itself. Messy, gestural grounds can be very appropriate for sketchbook exercises and, in many cases, provide welcome contrast to a tightly controlled observational drawing for which high school art students are well known. Textural grounds can also be used as a method for imparting texture to the objects within the artwork and for creating a visually interesting surface.

In the example to the right, by Jane Mitchell, a semi-translucent baby’s pram has been painted over a textural background – creating the impression of a decaying wall surface. The work suggests urban decay: forgotten moments in time; a snapshot of human existence in a crumbling, eroding world.

A pastel drawing exercise by Adiefineart:

Acrylic Washes / Ink Washes / Watercolour Grounds

Captivating work by Stella Im Hultberg:

Some of my favourite grounds are those produced with watery, unpredictable mediums. A watery paint, ink or dye, with all its wild splashes, irregular runs, seeping and pooling, is the stuff of magic. When making such a watery ground, you embrace a sense of freedom and endless possibility. Sometimes my students will spend a whole lesson – or an evening at home – making a pile of beautiful, splashy, crazy grounds. They get thick, wet-strength paper (300gms, for example) – or scraps out of the bin – or other random things (see the previous article in this series for ideas) and dunk bits in water, ink or acrylic wash and lay them, dripping, on a table. Then they splash colour everywhere; splatter a fine mist of inky rain.

Beautiful Indian ink splatters by Lisa Sarsfield:

An eye-catching image by graphic designer Graham Smith:

Artist Andrew Young, with drips that have run off the painting and onto the wall:

Crackle medium

Crackle medium can be used to create a ground that has an ‘old’ weathered appearance. Dry-brushing can be used to exaggerate the appearance of the cracks. While care should be taken to avoid using mediums like this just for the sake of it, this can be a fun medium to experiment with.

Image sourced from a great tutorial about how to make homemade crackle medium using glue by Makethebestofthings:

Shellac

Shellac is an ‘olden day’ varnish, available through art shops in the form of dried shellac flakes. It is amber in colour and can be used to seal an artwork prior to painting. It is usually applied after a sketch has been done, as shellac is translucent, and the pencil lines show through (sometimes they smudge a little). It is usually necessary to complete any sketches first, as it is very difficult to draw onto shellac with a pencil, due to its shiny, hard surface. It is sometimes difficult to paint on too, as certain paints ‘peel’ off it.

Translucent Grounds

Gel medium can be particularly useful when painting over a surface (such as a map or speckled piece of timber) that has awesome marks that you want to keep.

Encaustic (wax mixed with oil paint) can also be used when working over old salvaged materials, as in the awesome example to the right by Janet Nechama.

In conclusion…

Using a ground often results in the creation of rich, multi-layered works that have a history to them; buried marks that fill them authenticity. Instead of being superficial or surface-deep, your painting becomes the work of an artist: filled with song.

This article is the second in a four part series about creative use of media for high school art students.

Read Part 3: Beyond the Brush.

Read Part 1: How to Make your Art Project Exciting!